Last week, I made Equion, one of my longest-running projects, open-source. Originally designed to help my friends and I easily discuss mathematics and video games in one place, it grew over the course of several months into a full-fledged chat platform. Now open source and with a production server open for new users, I thought it time to talk about how I built it, and why I eventually decided to make it open-source.

In this blog post, I’ll talk about the development of Equion and my design decisions, as well as discussing the individual services that make it work and how they interact.

But first, where did this all begin?

Why Equion?

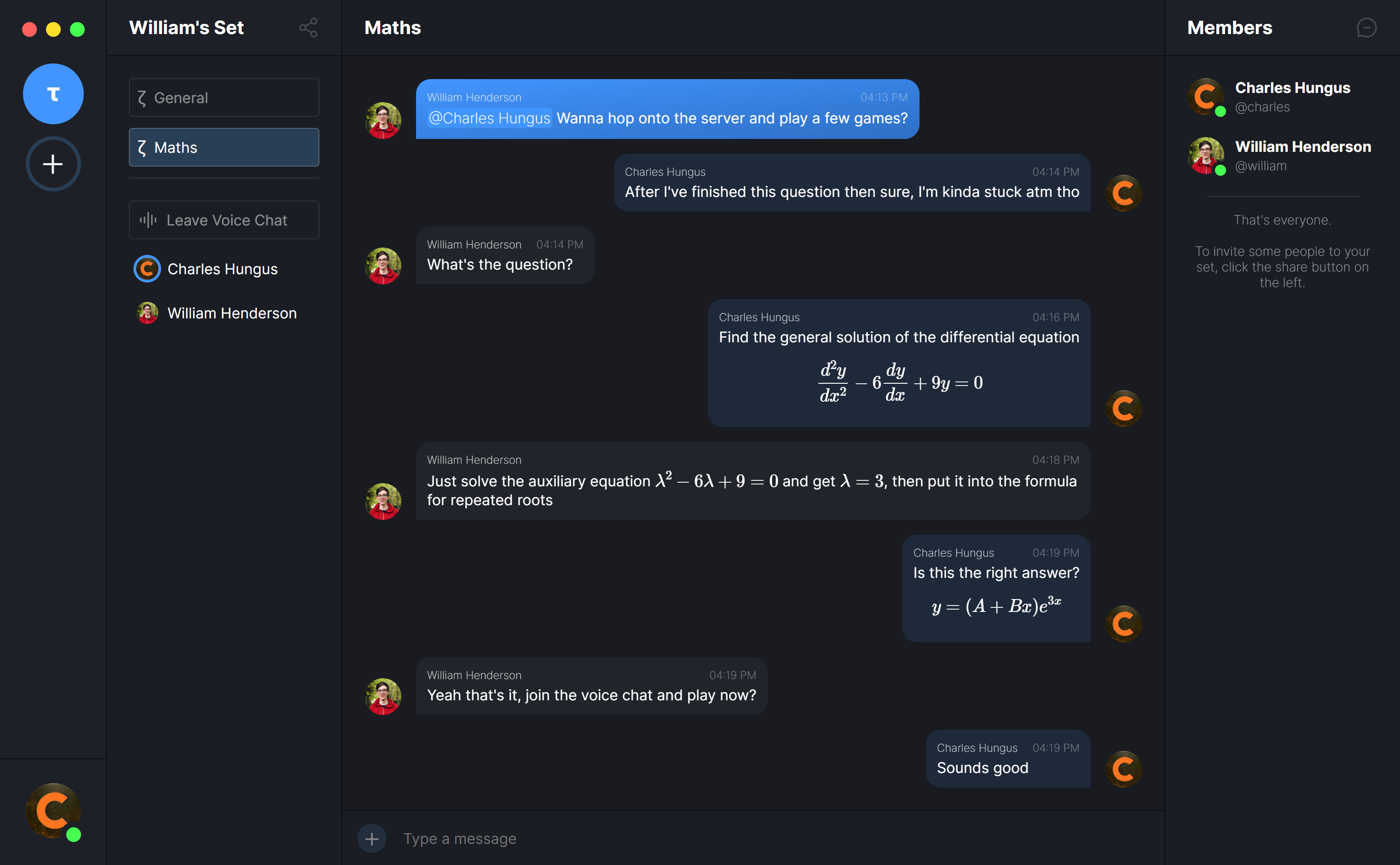

In early 2022, during the run-up to my A-level exams, my friends and I spent a fair amount of time revising, both independently and together. I took both Mathematics and Further Mathematics, so a lot of my work was focussed on the subject. While revision together in the library was very productive, we struggled to get the same kind of productivity working together online using Discord, which was predominantly due to difficulty communicating mathematical ideas through a platform that was very clearly not designed for them.

After several weeks of becoming increasingly exasperated every time I had to try to decipher differential equations written in plain ASCII, I decided that I had had enough, so I began building a new, Discord-like platform that would allow the use of LaTeX to display mathematical notation, while still providing us the capability to finish our revision and switch over to some video games without moving to Discord. The name Equion is a corruption of the word “equation”, which, prior to being the name of the platform, was an inside joke with my friends.

What does Equion do?

Equion is a platform that allows small, invite-only groups of people, called Sets (servers in Discord), to discuss mathematics and anything else together. Conversations can be categorised into Subsets (channels in Discord), which help to organise the discussion. Certain users may be admins of a Set, which gives them additional permissions to manage the Set and its Subsets. Admins may also manage Set invites, which are used to invite people to join the Set, delete messages, and kick misbehaving users. Each Set has a voice chat, which allows users to speak to each other in real time, as well as share their screens. Messages can be formatted using LaTeX or Markdown, and images can be attached. Certain websites have configured embeds, which allow users to share content from YouTube and other websites within the application.

Overall, Equion supports a similar feature set to Discord, but with a few key differences. Alongside its support for mathematical notation through LaTeX, Equion is tailored for small groups of people rather than for large communities.

The Architecture of Equion

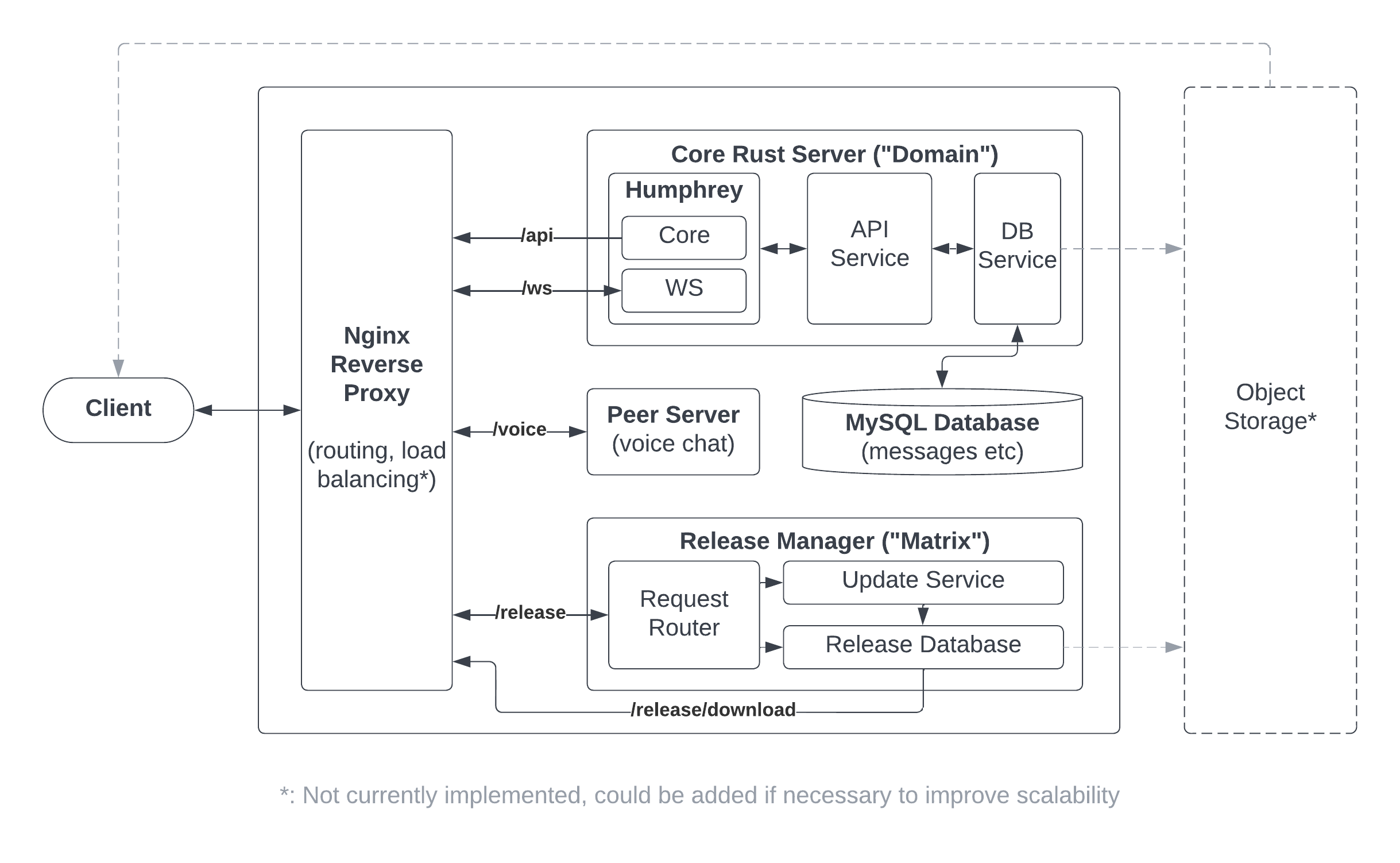

Equion is made up of a number of mathematically-named services, which are responsible for different aspects of the platform. These services are:

- Domain, the core Equion server, providing the API and interfacing with the database

- Range, the Equion front-end, providing the user interface

- Bijection, JavaScript bindings to the Equion API, used by the front-end

- Axiom, the Equion website

- Matrix, release manager, used to publish and retrieve Equion releases

- Database, the MySQL Equion database

- Voice, the PeerJS Equion voice chat server

- Gateway, the NGINX Equion gateway

For the remainder of this post, I’ll discuss the inner workings of some of these services, and how they interact. I won’t be discussing Matrix, as it is less relevant, fairly complex and could be a post in its own right!

The Front-End (“Range”)

Discord is built with Electron, a cross-platform framework which allows desktop apps to be built using web technologies. While very powerful, it is infamous for its high memory usage and large executable size due to it packaging an entire build of Chromium with every application. I knew I wanted to use web technologies, as I am already very familiar with TypeScript and React, but I really wanted to avoid Electron for the reasons above.

Tauri, a framework similar to Electron but written in Rust, has just reached its stable release, so I decided to try it out. It uses the operating system’s built-in web engine (WebView on Windows, WebKit on macOS) instead of Chromium, so applications built with it are very lightweight. Of course, being such a new project, the community is not as large as that of Electron and some things are still a bit fiddly to achieve, but I found that the performance benefits greatly outweighed the development drawbacks.

The front-end is built with React using TypeScript. For certain features, it calls Rust functions through Tauri. These include notifications, the tray icon, and file management.

Rendering LaTeX

Rendering LaTeX was one of the easiest parts of building Equion, surprisingly. I simply used the MathJax JavaScript library to render mathematical notation. However, this did cause some performance issues, so I ended up using regular expressions to identify messages containing LaTeX code and then using MathJax just on those messages.

Deep Linking

Deep linking is the mechanism by which a hyperlink on a website can be opened in Equion. This is used in Equion for invite links, so that when users visit an invite page in their browser, the page includes a button to “open in Equion” which allows them to join the Set.

While this is not supported in Tauri, I managed to find an unreleased Tauri plugin which implements it. After some testing, the plugin appeared very stable despite being unreleased, so I decided to use it. The plugin is called tauri-plugin-deep-link, and since it is unreleased, I had to specify it as a Git dependency and lock the commit.

[dependencies.tauri-plugin-deep-link]

git = "https://github.com/FabianLars/tauri-plugin-deep-link"

rev = "4e014f28767f69d097b59e1b40ca3384d94b0029"

When a deep link is clicked, the plugin will process it, bring the Equion window to the front, then send a message to the TypeScript front-end to open the invite dialog.

The Back-End (“Domain”)

The Equion server is built using my Humphrey suite of Rust crates, which are all open-source. It uses Humphrey Core to provide HTTP API endpoints, Humphrey JSON for JSON encoding and decoding, and Humphrey WebSocket for real-time communication.

The Pub-Sub Architecture

Communication between the clients and the server uses a kind of topic-based publish-subscribe architecture, in which each client requests data from the server very sparingly, instead relying on the server to publish updates to clients who are interested in that data. The only times the client explicitly requests data are when the user first loads Equion, and when the user loads non-real-time data such as historical messages or user profile information. Clients subscribe to events for specific Sets, and the server publishes updates in the form of JSON events.

There are specific events corresponding to the creation, updating, and deletion of Sets, Subsets, and messages. There are also separate events for users joining and leaving Sets, as well as updating their profile. The joining and leaving of voice chats makes up another event. Finally, there is an event for when a user begins typing in a Subset.

For example, when a user renames a Subset, the server publishes the following event to all clients subscribed to the Set which contains the relevant Subset:

{

"event": "v1/subset",

"set": "Set ID",

"subset": {

"id": "Subset ID",

"name": "The updated name of the Subset",

},

"deleted": false

}

If you’re interested, the entire event system is documented in the Equion API docs.

I chose to use this architecture because it is able to ensure that all online clients always have the most up-to-date information without too much additional overhead. Furthermore, it would be much easier to scale horizontally if necessary than other approaches, since servers could communicate with the same event system as clients over something like Kafka. This is not something I have implemented yet, but I would be interested in exploring it in the future.

Changing State

When the user wants to change the state of the server, for example sending a message, logging in, or creating a Set, the client makes a request either through WebSocket or through the HTTP API. In order to get real-time updates, the client must have a WebSocket connection open with the server, and this connection can be used both ways.

For this example, I’ll be demonstrating how Equion signs in a user through both HTTP and WebSocket. Using the HTTP API, a POST request must be made to the /api/v1/login endpoint, with the following body:

{

"username": "example",

"password": "hunter2"

}

The server will return a JSON response with the following information:

{

"success": true,

"token": "User token",

"uid": "User ID"

}

If the login was unsuccessful, success will be set to false and an additional error field will contain an error message. This is the same for all API endpoints.

The only difference between the HTTP and WebSocket methods is that over WebSocket, it is necessary to also provide the API command as part of the JSON message.

{

"command": "v1/login",

"username": "example",

"password": "hunter2"

}

In order to link up WebSocket responses with their requests, a unique ID can optionally be supplied with a WebSocket message. This ID will be returned with the response, allowing the client to match up the response with the request, and resolve the corresponding promise.

Voice Chat

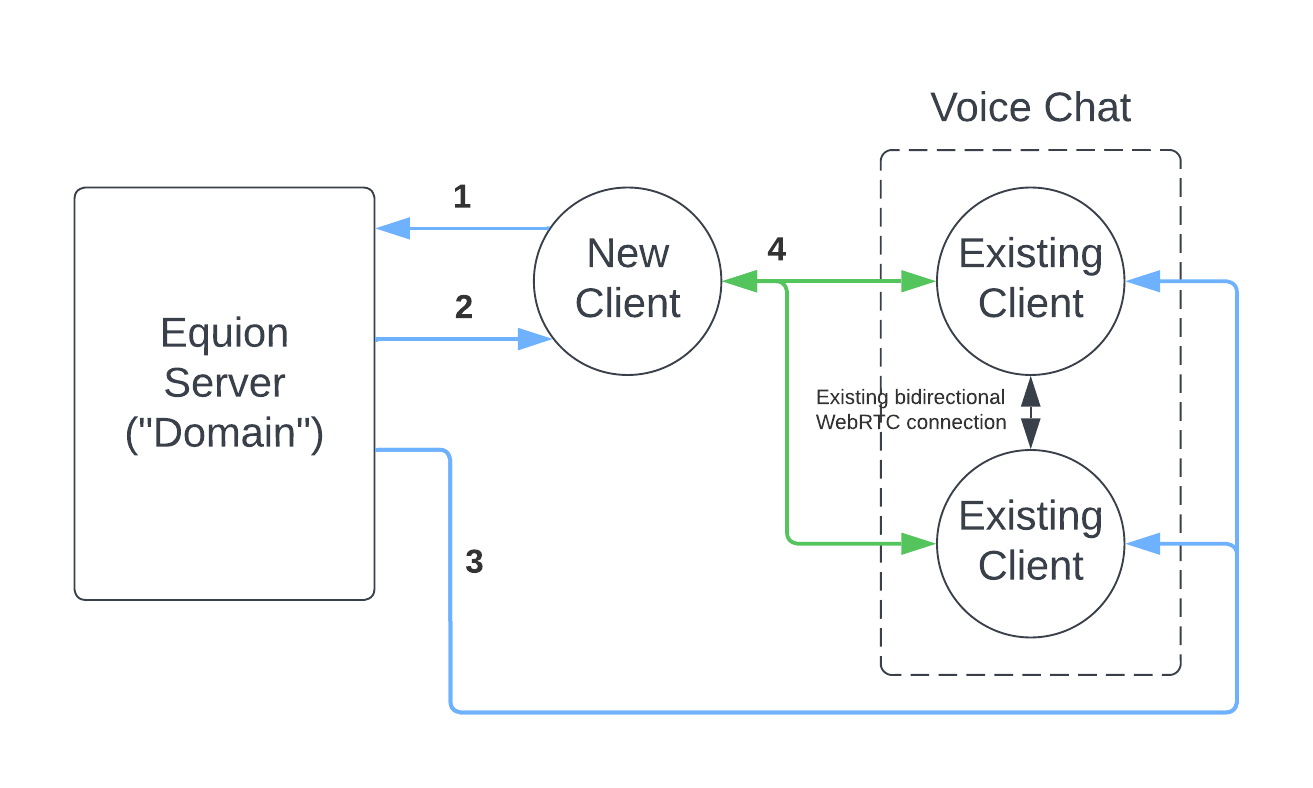

A key feature of Equion is the voice chat. This is a real-time peer-to-peer communication system which runs over WebRTC, using PeerJS. The server is responsible for managing the voice chat, but the actual connections between members of the voice chat happen fully on the client side. I chose to use PeerJS as I was already somewhat familiar with it, and it made it a lot easier to get WebRTC to work.

When a user joins a voice chat (1), the server tells them the peer IDs of all the other members currently in the voice chat (2). The server also informs the other members of the new member’s peer ID so they know to accept the WebRTC connection (3). This is necessary to prevent unauthorised connections, as the connection happens client-side. The client then establishes WebRTC connections with the other members, which they accept (4). All of this takes place over WebSocket, except the final step, which happens using WebRTC.

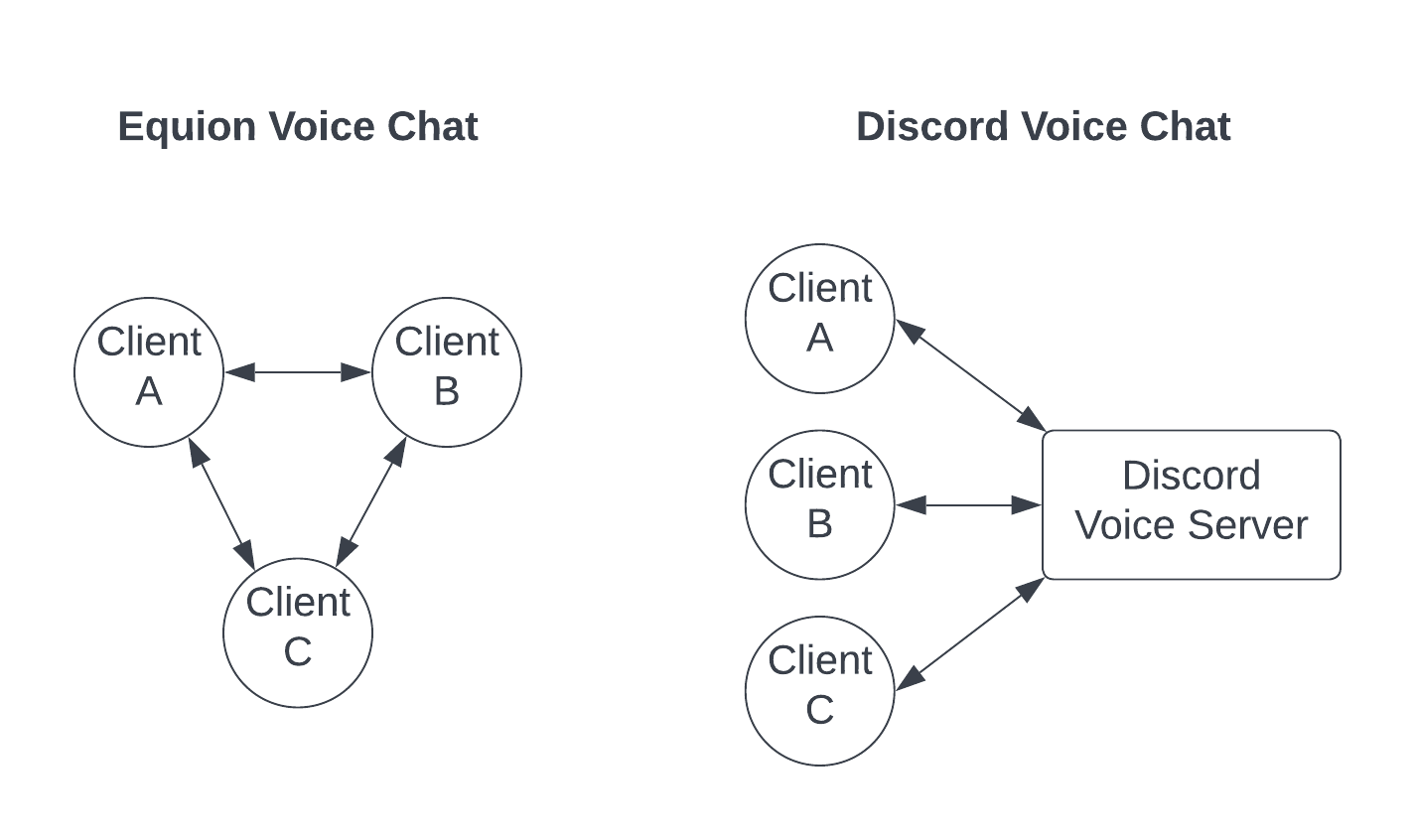

Discord has a similar system, but it uses a dedicated voice server between the clients. This has the advantages of being able to use one WebRTC connection to transmit all the members’ audio instead of one per member, which allows for much larger voice chats, as well as hiding the IP addresses of the members. However, it has much higher latency since the audio must travel through two WebRTC connections instead of just one, and since Equion is designed for smaller groups, I decided not to use an intermediate voice server. This approach did make it a lot easier to implement things like controlling the volume of specific users and having a circle around those who are talking, as this can be done completely client-side.

Screen Sharing

Screen sharing was implemented in a very similar way. When a client wants to share their screen, they simply establish an additional video WebRTC connection with every client, which the recipients identify as a screen sharing stream. The UI is then updated to indicate that this stream is available to view, and clients can watch it by clicking the “Watch Screen Share” button. When the stream is ended by the sharer, the UI is updated again to indicate that the stream is no longer available.

Using Docker for Deployment

Equion was the first project where I really took advantage of Docker and Docker Compose in order to easily and quickly deploy the server. Since there are a number of services required for the server to work (Domain, Axiom, Matrix, Database, Voice and Gateway), I decided to use Docker Compose to manage them in a predictable and efficient way.

The Docker Compose file defines three volumes alongside the six services. One is for the actual database data, one for the built version of Axiom so it can be served by Gateway, and one for Matrix to store releases.

Gateway, using NGINX, proxies requests to the appropriate service depending on the URL. For example, /api and /ws requests will go to Domain, /release will go to Matrix, /voice to Voice etc. It also serves static content for Axiom, which is built as part of the Docker image build process.

Conclusion

As much as I tried to implement everything my friends and I wanted in a chat platform, there was one problem that I couldn’t overcome: Equion isn’t Discord. It might do almost everything that Discord does, much of it better than Discord, but it can’t replace Discord unless everyone uses it.

I should’ve seen this problem from the start, but being so eager to build our own chat platform, my friends and I didn’t think about it. Sadly, we don’t really use Equion anymore, even though it’s perfectly good enough for our group’s needs.

I decided to open-source Equion because I realised that it is much more valuable as a portfolio project than a private, relatively-unused service for my friends. Furthermore, by being open-source, anybody can learn from my work and use it themselves. Who knows, maybe someone will find themselves in the same situation as I was, and it’ll help them revise too!

Thank you for reading this post. If you found it interesting, please consider sharing it with others who may be interested!