Plenty of people have already written about how to learn to program, but there are comparatively few resources targeted at developers who already have experience of programming and want to learn a new language. In this post, I’ll be discussing some important things to keep in mind when learning another programming language, and then the approach I take when doing it myself.

Introduction

Having recently started my first year of Computer Science at Cambridge, I’ve spent a lot of time in the last few months learning new languages as it seems like almost every course is taught in a different one! This led me to think more deeply about the actual process of learning a programming language, and I thought what I found was interesting enough to warrant a blog post. This term I have two programming courses, Foundations of Computer Science (in OCaml) and Object-Oriented Programming (in Java, unsurprisingly), so I’ll be using these as examples throughout this post since they’re the most recent languages I’ve learned.

I’ll start by discussing a few abstract points about learning a new language, then move on to how I take these into account when doing so.

Syntax is the easy part

I’ve come to realise that, as someone who has been programming for quite some time, learning the syntax of the language is only a very small part of learning a programming language. Of course, for someone who has never programmed before, getting the letters and symbols in the right place can seem a daunting task, but after learning that first language, the syntax of a new language is usually the easiest part to pick up.

For many mainstream languages, you can probably already read their syntax, so it’s just a case of remembering the keywords. For example, I’d never programmed in Java before last week, but I can already read and understand Java code to some extent because it’s quite similar to TypeScript, which I have a fair amount of experience in.

For languages with more unique syntax, like OCaml, it’s still not too difficult to get to grips with the syntax - there’s a bit more to remember, such as the initially-confusing difference between ;, ;; and in, but it’s still just a case of learning what each symbol means.

To illustrate my point, let’s take a look at this (highly inefficient) bit of code:

int f(int n) {

if (n <= 1) {

return n;

} else {

return f(n - 1) + f(n - 2);

}

}

Is this C? Or Java? Or C#? It could be any of them - the syntax is identical and therefore the code compiles as all three! However, it does not necessarily do the same thing in all three languages, which brings me to my next point.

Syntactic similarities are not always semantic similarities

Calling f(25) in Java will return the number 75025 - the 25th Fibonacci number, as expected. You’d think that calling it in C would do the same thing - with most compilers and on most machines, it would - but it’s not required to. It’s perfectly valid for f(25) to return the number 9489 as well.

But wait a second, that’s not the 25th Fibonacci number! How can that be? Well, in this case, it’s because the C specification only requires that the int type be able to store numbers between -32767 (yes, not -32768 for some reason) and 32767 inclusive, so a spec-compliant C compiler is free to use just 16 bits to represent an int. This leads to integer overflows, resulting in the wrong answer. With the Java implementation, the Java specification requires at least 32 bits to be used to represent an int, so we don’t encounter the overflow there.

In reality, of course, this is a contrived example since almost all C compilers will use 32 bits to represent an int. It does however illustrate the point that just because two languages have similar syntax, it doesn’t mean that they’ll behave in the same way.

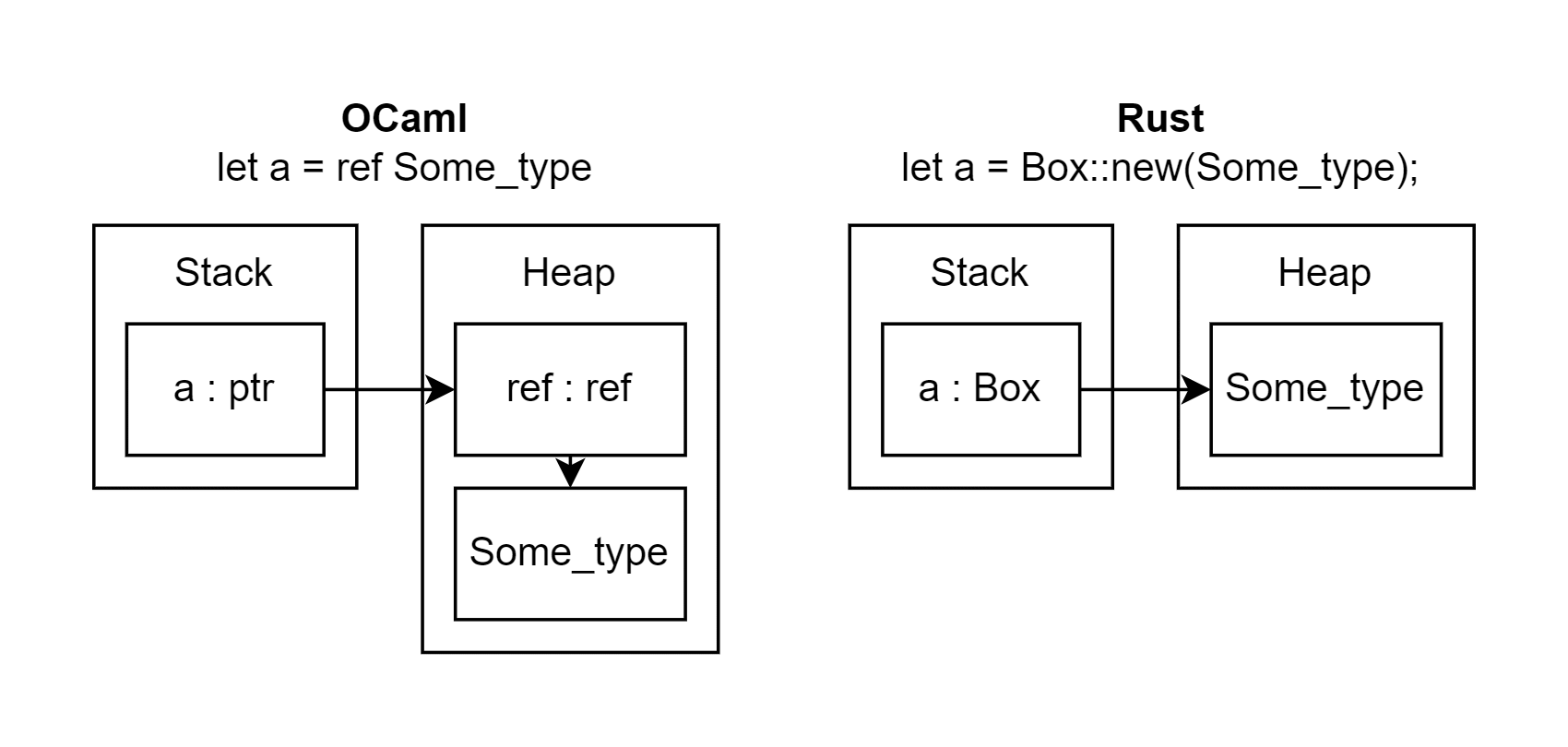

I was a victim of this kind of incorrect assumption myself when I was learning about references in OCaml. I knew that references were a way of storing a mutable value on the heap, and that they can be constructed using ref variable_name. In my head, I likened this to Rust’s Box::new constructor, which I knew to do the same thing of taking a value and storing it on the heap. However, there’s a subtle difference - in Rust, updating the value stored in a Box mutates the value on the heap, but in OCaml, updating the value creates a new value on the heap and updates the reference to point to it. This is because the mutability in OCaml’s reference is within the reference object itself rather than the value it points to, whereas in Rust it is the boxed value that is mutable.

This arises because the only stack-allocated (“unboxed”) values in OCaml are pointer-sized primitives, whereas in Rust, any type with a constant size known at compile-time (this is referred to as being Sized) can be stack-allocated. This is shown in the diagram below. You can read more about OCaml’s memory model here - it’s a really interesting read.

Anyway, I digress. The point is that it’s important not to make too many assumptions about how a language will behave based on its syntax and similarity to other languages you might already know. This is only really something you can learn through reading the documentation, since the bugs these differences can cause are subtle and can be hard to spot in practice. Making the mistakes I did has made me more careful about ensuring I understand exactly what the language is doing before I do it, rather than assuming that it works just like another language I know.

Be open to new ideas

When learning a new language it can be tempting to just program like you would in a language that you already know. For example, when I was first learning OCaml, I found myself wanting to write code like this:

let sum n =

let result = ref 0 in

for i = 1 to n do

result := !result + i

done;

!result

This is a valid way of writing the function, but it’s not very idiomatic and it goes against OCaml’s core principle of functional programming. As a primarily-functional language, the preferred way of writing the same function, making use of tail-recursion and immutability, would be:

let sum n =

let rec inner n acc =

if n = 0 then acc

else inner (n - 1) (acc + n)

in

inner n 0

At first, this looks horrible to someone who is only used to imperative languages, but it’s actually a lot more readable, idiomatic and efficient (admittedly it was only 3% faster on my machine for n = 100000000).

It’s important to write idiomatic code in a new language, since it will help you learn how the language works and make your code easier to understand for others. Learn how to effectively use classes and OOP in Java, recursion and pattern matching in OCaml, lifetimes and borrowing in Rust, etc. It’s the little quirks of each language that make them unique and interesting, so don’t be afraid to try them out.

My Approach

One of my favourite personal projects is Humphrey, a dependency-free HTTP server written in Rust. I’ve been working on it on and off for almost 18 months now, and I’ve learned a huge amount about Rust in that time. Of course, having spent so much time on it, it does a whole lot more than just serve HTTP requests, but the other features aren’t important for this post.

My current approach to learning a new language is to rewrite Humphrey in it, albeit with a much smaller set of features. I’ve been doing this in OCaml (HumphreyJr) and in Java (Humphrey4j, not open-source yet), and it’s really helped me to learn some fairly advanced features of both languages. I always follow the unofficial and very vague “Humphrey spec” that I wrote out in a text file a few months ago, which is as follows:

- Must serialise and deserialise HTTP messages into appropriate data structures

- Must allow for the creation of HTTP responses in a flexible and idiomatic way

- Must provide a library for building web applications

- Must allow different routes to be configured in an idiomatic way

- Must allow state to be shared and modified between requests

- Should allow wildcards in routes

- Must provide an executable that serves the files in the current directory

- May provide more configuration options

- Must not use any third-party dependencies

- Except for TLS support

- Must have comprehensive test coverage

- Should be multi-threaded

Of course, this is a very small subset of the features that Humphrey actually has, but it’s complex enough to really get to grips with a new language.

Before starting to write the program, I always read at least the first few chapters of a book or guide on the language to get a feel for the syntax and the tooling. Then, I start by writing the HTTP request parser, since it’s a fairly simple place to start.

How is this helpful?

Each aspect of the project helps me to learn a different aspect of the language.

The HTTP request and response parser is a good place to start because I have to learn about the basic syntax and control flow of the language. I also have to learn about error handling and how to deal with the possibility of invalid input. I also have to learn about the standard library and how to read input from and write output to a socket.

Building a library teaches me about how to structure code in a modular way, and how packages work in the language. Allowing state to be shared between requests teaches me about generics and mutability, as well as thread-safety. Allowing wildcards in routes is just an exercise in implementing a simple wildcard-matching algorithm, but this is always a useful thing to do to get to know any programming language.

You’ll notice that a lot of the requirements in the spec are intentionally vague (“appropriate”, “idiomatic”, etc.). This is because, as I mentioned earlier, learning what is appropriate and idiomatic in a new language is very important, and this is something that requires further reading rather than just writing code.

For example, in the OCaml implementation, I chose to use functions to represent request handlers, with something similar to the following type:

type 'a handler = request * 'a -> response * 'a

This denotes a function that maps a request and some state to a response and some new state. I chose this approach because, as a functional language, a pure function seemed the best way to represent the operation of processing a request, instead of having side-effects to change the state.

In contrast, in the Java implementation, I chose to use an interface to represent request handlers, with a similar signature to the following:

public interface Handler<S> {

Response handle(State<S> state, Request request);

}

This denotes a generic interface that can be implemented by any class that wants to handle requests. The State class is a wrapper around the actual state, allowing mutable state to be shared between requests.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while learning another programming language is undoubtedly easier than learning your first, it’s a very different yet equally rewarding experience. Many of the traps to fall into are self-inflicted, such as making assumptions about how the language works, so it’s important to find a balance between applying your previous knowledge and learning the new language “from scratch” to avoid these misunderstandings. Undertaking a sufficiently complex project is my favourite way to learn a new language, while still referring to the documentation and other resources to ensure that I’m writing idiomatic and efficient code.

I hope this post has been helpful and if you found it interesting, please consider sharing it with others who may be interested too! Thank you for reading.