Over the Christmas break, I’ve been working on a game engine called TSGL, using TypeScript and WebGL. Last term I took a course on computer graphics, so I thought it would be a good way to solidify my knowledge, as well as giving myself something fun and somewhat useful to do alongside just studying! I’ll be writing a full blog post about the engine at some point, but for now I want to discuss what I think was a fascinating rabbit hole I went down while trying to fix a bug.

In this post, I’ll be talking about how V8’s garbage collector works, and then I’ll be investigating how it interacts with WebGL. Finally, I’ll discuss the bug that was in my code and how I fixed it.

What is Garbage Collection?

Garbage collection is a way of managing memory in a program. In some languages, such as C, the programmer is responsible for manually allocating and freeing memory. This is very efficient, but it’s also very error-prone, which can lead to at best memory leaks and at worst severe security vulnerabilities.

In garbage-collected languages, a garbage collector is responsible for freeing memory when it’s no longer needed, i.e. when it can no longer be accessed by the program. This means that the programmer doesn’t have to worry about manually freeing memory, but it can also lead to performance issues since the program must be paused periodically to perform the garbage collection. If lots of memory is allocated and freed quickly, this can lead to a lot of sometimes long pauses, which can be very noticeable to the user.

Of course, other approaches to memory management exist, like Rust’s lifetimes (which I won’t be discussing here, but I encourage you to read about because they’re awesome). However, garbage collection is probably the most common approach.

Mark and Sweep

The most basic garbage collection algorithm is called mark and sweep. The algorithm works in two stages. In the mark stage, the garbage collector traverses the root set (i.e. the set of pointers that are known to point to live objects, such as those on the stack and global variables), and recursively follows pointers to mark all reachable objects as in-use. Then, in the sweep stage, the garbage collector scans the whole heap, and frees all the unmarked objects.

This algorithm is very simple, but it requires the program to be paused for the whole duration of the garbage collection. In addition, the entire heap must be scanned, which can be slow. For these reasons, modern garbage collectors, such as that of V8, use more sophisticated algorithms.

Semi-Space (Copying)

Another common garbage collector design is called the semi-space collector. This algorithm works by splitting the heap into two equal-sized spaces, called from-space and to-space. Objects are allocated in to-space. When a collection begins, the to-space becomes the from-space and vice versa. The root set is recursively traversed, and all reachable objects (which are all in the from-space) are copied to the to-space and their pointers updated. Then, the from-space is freed.

This has the advantage that the time taken to perform the garbage collection is proportional to the amount of live data, rather than the total amount of data. However, it requires twice as much memory as other algorithms, since in the worst case (the heap is full and all objects are live), the entire from-space will be copied into the to-space.

V8’s Garbage Collector

V8 is the JavaScript engine that powers Chrome, Node.js, and many other JavaScript runtimes. It uses a generational garbage collector, which combines the advantages of mark and sweep and semi-space collectors.

Generational Garbage Collection

The basic idea behind generational garbage collection is called the generational hypothesis, which states that objects created most recently are also most likely to become unreachable soon.

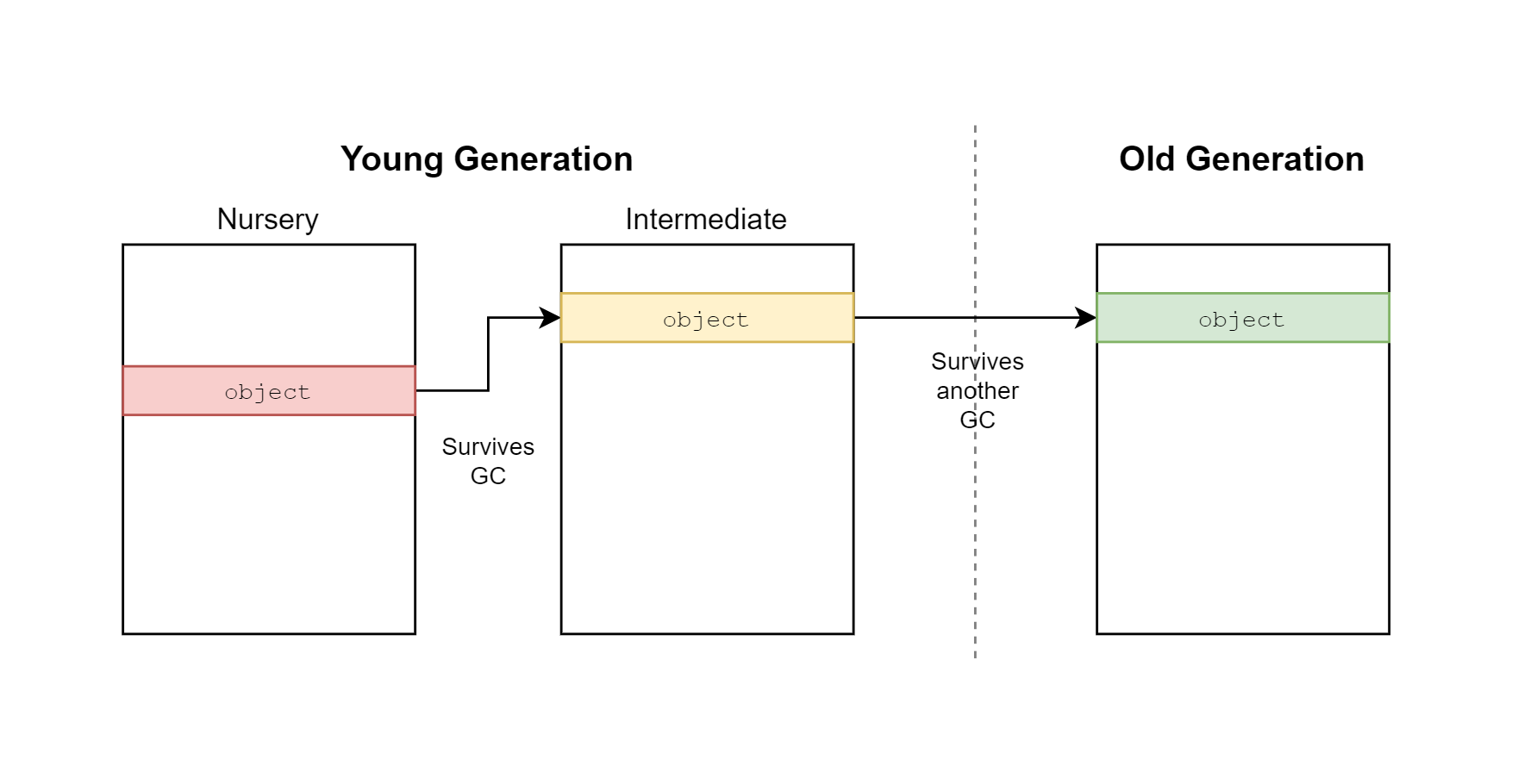

The heap in V8 is split into two generations, the young generation and the old generation. The young generation is further split into the nursery and the intermediate generation. All objects are initially allocated in the nursery. If an object survives its first garbage collection, it is promoted to the intermediate generation. If it then survives another garbage collection, it is promoted to the old generation.

The V8 garbage collector has two parts, one for each generation. The young generation is collected using a semi-space collector, while the old generation is collected using a mark and sweep collector. This means that the young generation can be collected very quickly and frequently, while the old generation is collected less frequently and takes longer. According to the generational hypothesis, the old generation should rarely need collecting, so this is a good trade-off.

Minor GC (Scavenge)

The young generation uses a semi-space collector, called the “Scavenger”.

The result of a minor GC is that all live objects in the nursery are promoted to the intermediate generation, and the nursery is left empty. All live objects in the intermediate generation are promoted to the old generation.

The issue with this is that by not scanning the entire heap, the garbage collector can’t find pointers to the young generation from the old generation. Of course, V8 doesn’t want to traverse the entire of the old generation to do this for every minor GC, because that would defeat the purpose of separating the generations. Instead, V8 uses a write barrier, which is a piece of code that is run whenever a pointer is written to. Whenever a pointer to a young object is written to a field in an old object, this is recorded in a table. Then, when a minor GC is triggered, the table is used as part of the root set.

V8 does the Scavenge mostly in parallel. The traversal of the root set is parallelised, in that newly-found objects are added to a global queue, which is then processed by multiple threads. While the execution of the program must still be paused, the parallel nature of the algorithm means that the pause is much shorter than it otherwise would be. You can read more about the Scavenger in this V8 blog post.

Major GC (Mark and Sweep)

When the heap starts getting full, a major GC is triggered. This is a mark and sweep collection across the entire heap, including the old generation. Compaction is also performed, which means that live objects are rearranged in memory to reduce fragmentation. While this is happening, the program is paused, but part of the sweep stage is done concurrently with the execution of the program to minimise the pause time.

You can read more about the V8 garbage collector in this V8 blog post.

WebGL and Garbage Collection

You might be wondering why I’ve spent so much time talking about the internals of V8’s garbage collector. Well, it turns out that the interaction between V8’s garbage collector and Chrome’s implementation of WebGL is very interesting. WebGL is a JavaScript wrapper around OpenGL ES, which is a low-level graphics API. It’s used to render 3D graphics in the browser using the GPU.

When working on my game engine, I noticed that every so often I would get significant frame drops (we’re talking more than ten frames at a time, a couple of times a minute). I used Chrome’s built-in profiler to try and figure out what was going on, and I noticed that every frame drop occurred a couple of frames after a major GC, at which point the GPU thread was blocking for several hundred milliseconds. I was very confused, because I didn’t think that WebGL used the garbage collector at all, so I began looking into it.

Since code to interact with WebGL is written in JavaScript, it’s still executed by V8 and still subject to the same garbage collection rules as any other JavaScript code. However, WebGL makes heavy use of opaque handle objects, which can be thought of as references to objects on the GPU. For example, when you create a texture in WebGL, you get back a WebGLTexture object, which is a handle to the texture on the GPU. Internally, this is just an integer that is used to identify the texture.

This leads to some problems when it comes to garbage collection. Since the WebGLTexture object, like all other WebGL objects, is a JavaScript object, it can be garbage collected just like any other JavaScript object. However, unlike a normal JavaScript object, it directly corresponds to an OpenGL object, which in turn corresponds to an object on the GPU. If the JavaScript object is garbage collected, what happens to the OpenGL object? What happens to the object on the GPU?

The WebGL specification has this to say:

“Note that underlying OpenGL object will be automatically marked for deletion when the JavaScript object is destroyed”

This means that when a WebGL object is garbage collected, the corresponding OpenGL object (and indirectly, the object on the GPU) is also marked for deletion. This raises the question of when the GPU object is actually deleted. The WebGL specification doesn’t specify this, so it’s up to the browser to decide. I couldn’t find any concrete answers to this question, so I did some experimentation.

When are WebGL objects deleted?

My hypothesis was that WebGL objects would only be deleted on the next major GC, despite potentially being garbage collected in a minor GC. Since the underlying OpenGL objects are completely separate from V8, I thought that perhaps Chrome detects when V8 performs a major GC and takes the opportunity to also delete the OpenGL objects that are marked for deletion.

To test this, I wrote a simple program that allocates a certain amount of memory and creates a certain number of WebGL textures each frame. The allocation of memory is done to trigger frequent minor GCs, and the creation of textures is to create a lot of WebGL objects. The very simple program is as follows:

function loop() {

let bigArrayToGC = new Array(4096).fill({ myKey: "myValue" });

for (let i = 0; i < 32; i++) {

let textureToGC = gl.createTexture();

gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, textureToGC);

gl.texImage2D(gl.TEXTURE_2D, 0, gl.RGBA, 1, 1, 0, gl.RGBA, gl.UNSIGNED_BYTE, new Uint8Array([255, 255, 255, 255]));

gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, null);

}

gl.clearColor(0, 0, 0, 1);

gl.clear(gl.COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

requestAnimationFrame(loop);

}

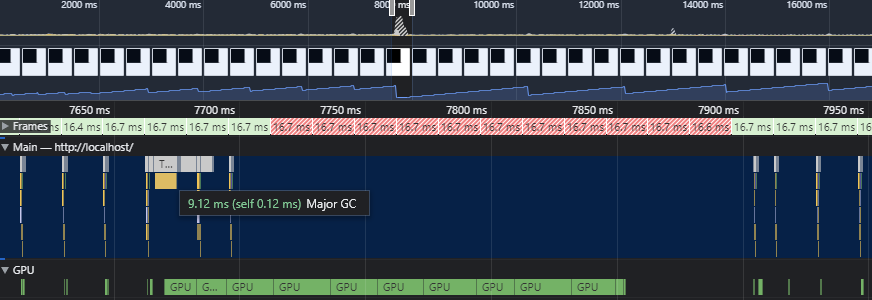

Using the profiler, I ran this code, and exactly what I thought would happen did indeed happen:

After about 8 seconds, the first major GC happens, and a few frames later, the GPU thread blocks for a long time and as a result 11 frames are dropped. This indicates that my hypothesis was correct, and that the WebGL objects are indeed only deleted on the next major GC. I wasn’t able to find any sources to prove or disprove the other part of my hypothesis, that Chrome explicitly listens for major GCs to do this, but I think given this result it’s a safe assumption.

Interestingly, the only reason a major GC is triggered is because the new Uint8Arrays created when initialising the texture to a single white pixel don’t seem to be collected by the minor GCs, so the heap slowly increases in size. If they are replaced with new Array(4).fill(255) (which has the same effect), then the minor GCs collect everything and no major GC is ever necessary. I can’t find any documentation on why this is the case, but if you happen to be an expert on V8’s garbage collector, please let me know (and sorry about any mistakes I have likely made in this post!).

ExternalPointerTable (EPT) which doesn't yet support minor GCs. The EPT is a memory safety feature: objects on the heap referring to things outside it have indices into the EPT instead of raw pointers, so even if some bug causes an attacker to be able to corrupt the V8 heap, no raw pointers are available to exploit to escape the sandbox! You can read more in this document. Thanks to Aapo Alasuutari for letting me know about this!

My Problem

So, now we know how garbage collection works in V8, and the basics of how it interacts with Chrome’s implementation of WebGL, I can finally explain why I ended up down this rabbit hole in the first place.

To demonstrate the capabilities of my game engine TSGL, I created a simple infinite runner game. I’ll discuss this more in a future post, but for now, here’s a video of it running (after I fixed the problem, of course):

While I was developing the game, I found that a few times a minute, the game would freeze for several hundred milliseconds, completely ruining the user experience as the game relies on quick reaction times! Profiling led me to discover what I’ve just been talking about for this entire post, but that still left the question of where exactly in my code I was creating so many WebGL objects.

Of course, the culprit had to be somewhere in the render pipeline, as that’s the only part of the program that is constantly running after initialisation. I hadn’t run into the problem in previous demos of the engine, which led me to believe that it was something I had added recently that was causing the problem. However, it turned out that the problem stemmed from a very old part of the engine: the material system.

Since I’d added texturing to the engine, I hadn’t actually tested the engine without textures - I’d done loads of testing of the texture system but I hadn’t tried adding a textureless material after adding support for textures. When I implemented textures, I had just set the engine to use a default 1x1 white pixel texture if no texture was specified for each material. You might be able to see where this is going…

While I thought that my code was generating these default textures once for each material when they were first rendered, it turns out that I was actually generating a new texture for each material every frame! Part of my render code looked like this:

let texture = this.material.mapKd;

if (!texture || !texture.isLoaded()) texture = Texture.blank();

I was never assigning the newly generated blank texture to the material! I fixed this at first by doing exactly that, and the problem was solved. However, I realised that this was a bit of a waste of memory, as the same blank texture can be used across multiple materials, so I decided to cache it in the Texture class:

class Texture {

private static blankTexture: Texture | null;

// other fields and methods omitted

public static blank(): Texture {

if (Texture.blankTexture) return Texture.blankTexture;

let texture = TSGL.gl.createTexture()!;

TSGL.gl.bindTexture(TSGL.gl.TEXTURE_2D, texture);

TSGL.gl.texImage2D(TSGL.gl.TEXTURE_2D, 0, TSGL.gl.RGBA, 1, 1, 0, TSGL.gl.RGBA, TSGL.gl.UNSIGNED_BYTE, new Uint8Array([255, 255, 255, 255]));

TSGL.gl.bindTexture(TSGL.gl.TEXTURE_2D, null);

Texture.blankTexture = new Texture(texture);

return Texture.blankTexture;

}

}

This was what I ended up going with, and the game now runs perfectly smoothly!

Conclusion

I had a lot of fun (alongside tearing my hair out for a short while) debugging this problem, and I learnt a huge amount about garbage collection, V8 and WebGL in the process. I hope you enjoyed reading this post, and please share it with anyone else who might find it interesting!

References

If you want to learn more (from much more qualified people), here are the resources I used to help me debug my code and write this post:

- Peter Marshall, Trash talk: the Orinoco garbage collector, 2019

- Ulan Degenbaev et al., Orinoco: young generation garbage collection, 2017

- Jay Conrod, A tour of V8: Garbage Collection, 2013

- Thorsten Lorenz, V8 Garbage Collector, 2018

- WebGL Specification