If you have a passport, chances are it’s insecure. Within a decade, it’ll probably track your every move too. In this post, I’ll be discussing the security and privacy implications of the biometric passport, a number of vulnerabilities in its security mechanisms, and what lies ahead for the future of passports.

This post is based on a talk I gave at Cambridge this term (which you can watch here), but here we’ll be leaving out the most technical details and focusing on the big picture… and it’s a scary one.

What is a biometric passport?

A biometric passport, or e-passport, is a passport that has a chip containing biometric data. This includes at minimum a digital photograph of the passport holder, and a copy of the data printed on the passport, all digitally signed by the issuing country. Countries may also include fingerprints, iris scans, or pretty much whatever other information they want.

Let’s imagine it’s 1am and you’re standing in the long queue for the e-gates at Stansted, reading a paper about attacks on biometric passports and getting progressively more concerned about using an e-gate (this is a completely arbitrary example that is in no way based on personal experience). When you finally reach the front of the queue and face your fears, the e-gate does a lot of things:

-

Using optical character recognition (OCR), it reads the machine-readable zone (MRZ) of the passport.

-

Using cryptographic keys derived from the MRZ, it authenticates with the passport chip and establishes a secure channel.

-

It reads the data from the chip and verifies the digital signatures.

-

The digital photo is compared to the photo taken by the e-gate using some fancy facial recognition stuff that I’m not going to talk about.

-

The system checks if the holder is banned from the country or on any watchlists, and if not, it opens the gate.

Basic Access Control

How does this handshake work? The answer is Basic Access Control (BAC), a protocol that establishes a shared secret between the passport and the e-gate which is used to secure future communications. I say “secure”, but as we’ll see later, the combination of Triple DES encryption and a short MRZ means that it’s not very secure at all.

Two document access keys are derived from the MRZ, one for encryption and one for authentication. The e-gate and the chip exchange nonces (numbers used once, used to prevent replay attacks) and keying material, using the document access keys to ensure the integrity and confidentiality of messages, and eventually settle upon a shared secret, which is used to derive the two session keys.

These keys are then used in Secure Messaging (SM), a protocol that basically just encrypts and signs messages between the e-gate and the chip, using Triple DES for encryption and a MAC (message authentication code) for authentication.

So what’s the problem?

Where do I start? Since the biometric passport was standardised in 2006, a number of vulnerabilities have been found, ranging from dodgy implementations to fundamental flaws in the design of the system. Here are three of my favourites.

The MRZ is way too easy to guess

When biometric passports were first introduced, many countries seemed to think “wow, this is great, we’ll just implement the standard and our passports will be more secure”. Unfortunately, the security of the system relies on the entropy of the MRZ, which is a combination of the passport number, date of birth, and expiry date.

At the time, many countries were using sequential passport numbers, meaning it only takes knowledge of a few passports to get an idea of the dependency between the passport number and expiry date. Furthermore, by estimating the age of the passport holder to narrow down the date of birth, it’s possible to reduce the number of possible combinations by a huge amount.

This allows our first attack: brute-forcing the MRZ. By eavesdropping the communication between the e-gate and the chip (which can be done from a few metres away), we can brute-force the handshake and recover the MRZ, and therefore decrypt the rest of the communication. This attack was demonstrated in 2007 by Liu et al. in E-Passport: Cracking Basic Access Control Keys, taking less than 30 seconds to crack German and Dutch passports using specialised hardware.

And remember - this was 2007! Even though sequential passport numbers have been largely phased out since then, we have orders of magnitude more computing power available to us now, and the MRZ is still far too short and the encryption far too weak to be considered secure.

The movements of an individual can be tracked

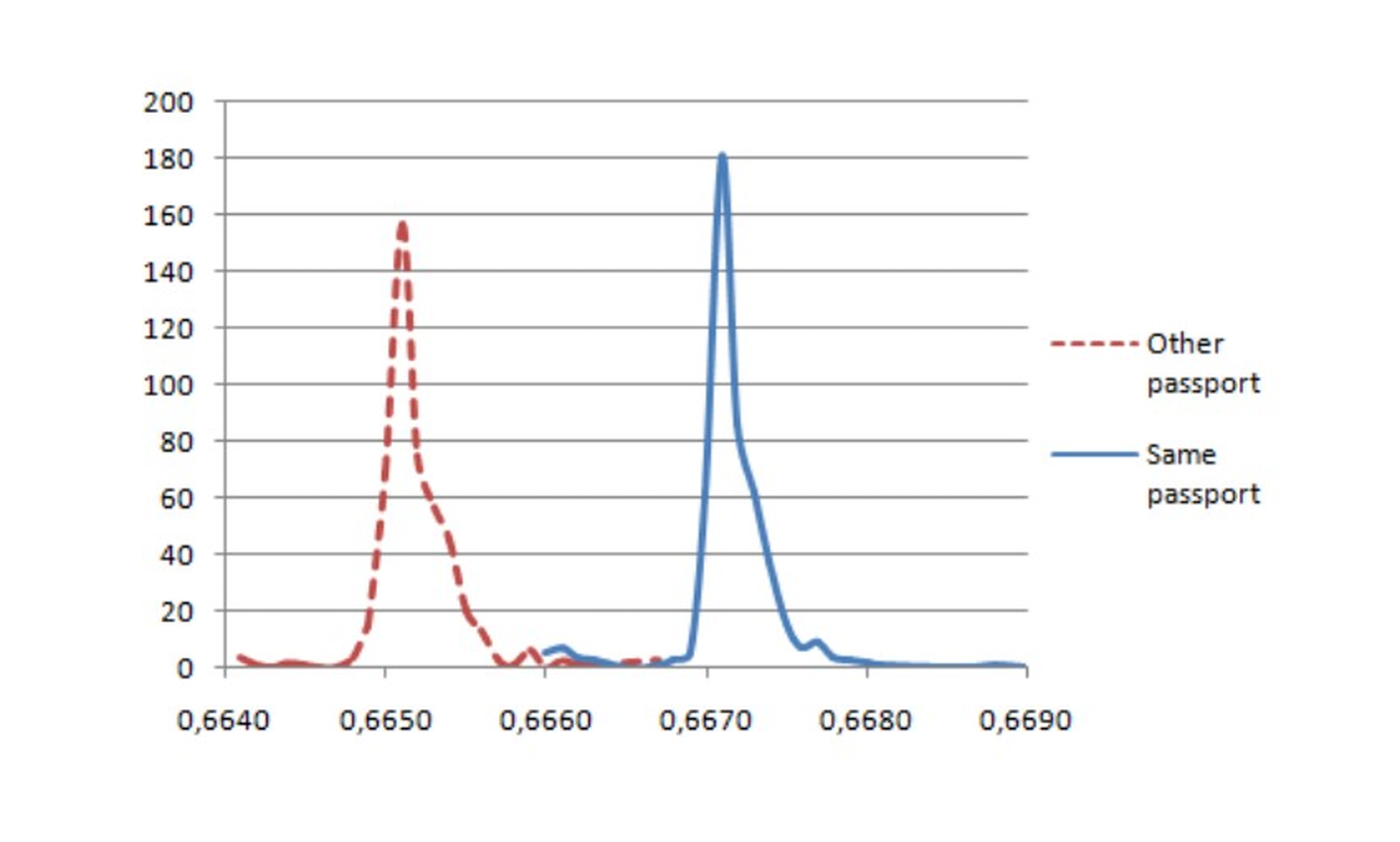

As I mentioned before, communications with the e-gate are signed. During the handshake, when we also include a nonce, this means that the chip must check both the nonce and the MAC before it can respond. You might be able to see where this is going: if we send a message with a valid MAC, the chip will take longer to respond than if we send random data. But how do we get a valid MAC?

Well, why do we need the nonce? It’s to prevent replay attacks: during a legitimate communication, all the messages will have valid MACs!

All we need to do is record a message from the handshake during a legitimate communication, and we can play that back to the chip and see how long it takes to respond in comparison to random data. Of course, this is a critical flaw in the chip’s implementation - it should take the same amount of time to respond to a valid message as it does to an invalid one.

The difference in response time between a valid and invalid MAC

This can be used to identify a specific passport, as a message intercepted from a different passport will have an invalid MAC and effectively be random data. This was demonstrated in 2010 by Chothia et al. in A Traceability Attack against e-Passports.

An attack like this was actually foreseen by the US government during the development of the biometric passport. One of their fears was that biometric passports would give terrorists the ability to develop a bomb that would be detonated by a US passport going near it. To mitigate this, they insisted that the US passport have a thin metal mesh embedded in the cover so that the chip could only be read when the passport was open. Why this wasn’t adopted by other countries is a mystery to me! Anyway, this attack doesn’t quite allow a detonator to identify the country of the passport, but it could certainly pick out a specific diplomat.

Just as a little aside, the French passport had even more interesting results: it went against the spec and would explicitly give a different error code for the two cases, removing the need for the timing analysis altogether and giving a 100% successful identification rate! Oops.

Combine the two and you don’t even need to eavesdrop

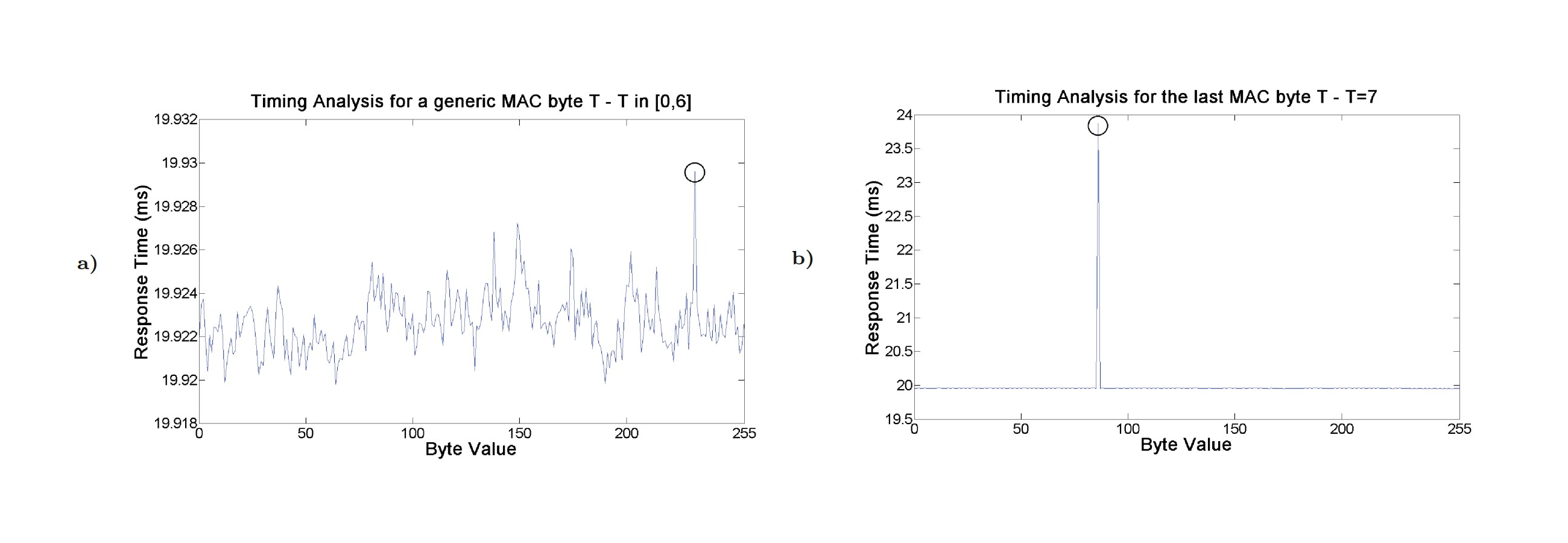

The timing analysis doesn’t stop at just identifying whether the MAC is correct or not. At a higher timing resolution, Sportiello found in his 2014 paper ePassport: Side Channel in the Basic Access Control that it’s possible to identify the specific byte that’s incorrect, and therefore brute-force the MRZ without even eavesdropping the communication.

By generating a random message and a random MAC, we can work through the MAC byte-by-byte, timing how long it takes for the chip to respond to with each possible value of that byte over a number of iterations, and choose the value that causes the longest mean response time. Once we’ve found the valid MAC for our random message, we can use that to brute-force the MRZ.

Identifying the correct byte (5000 iterations on the left, 500 on the right because the last byte makes a bigger difference, as used by the previous attack)

There are two reasons this attack is the most concerning. Firstly, there are still valid passports in circulation that are vulnerable. Secondly, it doesn’t require eavesdropping a legitimate communication, which means that the effort required from attackers to steal someone’s passport data is much lower and the attack scales much better.

However, an interaction with the passport of around 85 hours is required to find the valid MAC, so it’s not like someone standing behind you in the queue at Stansted can steal your passport data. That being said, modern smartphones are more than capable of performing this attack, as the NFC chip can be used to communicate with the passport, as I demonstrated in my talk. All it takes is a simple piece of malware and a few days of charging your phone near your passport, or your phone and passport being in the same bag, and your passport data can be remotely compromised. The malware could even be used as part of a relay attack, where your passport’s chip communicates through the internet to a fake passport at an e-gate, allowing the attacker to travel on your “stolen passport” without even stealing it.

Okay, what now?

The specific vulnerabilities I’ve discussed have (hopefully) been patched, but they mostly rely on the fundamental flaws of the system, which are still present. What are we to do about the fundamentally insecure design of Basic Access Control?

Well, get rid of it!

Password Authenticated Connection Establishment (PACE)

Based on Diffie-Hellman key exchange and using AES for encryption, PACE is a protocol that allows the e-gate and the chip to generate strong session keys, regardless of the strength of the MRZ.

This solves all our problems, right? Well, not quite. While EU passports since 2014 have been required to support PACE, BAC was only made optional in 2018, and all the passports I tested still supported it in 2023. If PACE is used at the e-gates, which I strongly suspect it is, then eavesdropping is no longer possible, but other future attacks on BAC could still be.

The Future of Passports

In 2021, ICAO (the International Civil Aviation Organization, which standardises passports) released an updated standard, introducing LDS2 (Logical Data Structure 2). This is a new section of the passport chip that allows the storage of further data, including travel history, visa records, and additional biometric data.

LDS2 completely changes what a passport is. Current passports are read-only, but with LDS2, they become writable. Passport stamps and visas become digital. Passports go from being an identification document to a detailed record of your movements.

At present, some countries allow you to request that stamps and visas are issued on a separate piece of paper, preventing you from being denied entry to one country because you’ve been to another. If travel history is enabled by the issuing country in LDS2, this will no longer be possible - according to the standard, it becomes mandatory for countries to “digitally stamp” your passport. When you return home, the e-gate at Stansted can upload your travel history to the Home Office.

I suppose this is good for national security, but is it worth it given the privacy implications?

Another issue is the free-form text fields in entry/exit records. Countries can mark people as “suspicious” with no explanation, and there’s no way to remove these records from your passport. In effect, any country can, for any reason, make it much harder for the holder of the passport to travel.

Conclusion

Biometric passports play a vital role in facilitating efficient and secure international travel, but they are far from perfect. While key security issues are on their way to being fixed, the privacy issues are just getting started. We’ll have to wait and see what the future holds!

As I mentioned at the start, this post is based on a talk I gave at Cambridge this term, which you can watch here. You can download my slides (which contain all the references for the talk and this post) here - I really recommend having a look at the three papers for the attacks, they’re fascinating.

Thank you for reading this post, I hope it made some sense! Feel free to share it with anyone you think might be interested, and if you have any questions or comments, please send me an email at hello@whenderson.dev.