A few weeks ago, I watched a video introducing me to Hugo, a static site generator written in Go that calls itself “the world’s fastest framework for building websites”. I thought that sounded like an interesting challenge, so for the past few weeks I’ve been working on a static site generator called Stuart, with the goal of being faster than Hugo.

In this blog post, I’ll be talking about how I built Stuart, and then I’ll be discussing the results of some benchmarks I ran to compare it with Hugo. Finally, we’ll look at how I migrated this blog to use Stuart.

But first, what is a static site generator?

What is a static site generator?

A static site generator, or SSG, is a program that creates a static HTML website from templates and data. The data is often formatted using the Markdown markup language, and the templates are written in a templating language. Static site generators are often used to create blogs, documentation sites, and other websites that serve mainly static content, as opposed to web apps which are dynamic and are more suited to frameworks like React, or even server-side rendering.

Static site generators are useful because they allow content to be written in a simple format without worrying about the layout or styling of the website, because the SSG automatically fits the content into defined layouts and styles. Since they output static HTML, websites built with SSGs are very fast to load as they don’t need to be rendered on a server or run any JavaScript.

Designing Stuart

At its core, a static site generator can be thought of as a function - albeit not a pure one - which maps input files (templates, data, static content etc.) to output files (HTML). I found this notion very helpful when designing Stuart, as I could build the whole system around this function. As I developed the project, it became clear that the build process could be broken down into three main stages: parsing, processing (where the function is applied), and saving. Before and after these three stages of the build, Stuart can be configured to run custom build scripts which integrate with the build process. These can be used to perform tasks such as compiling Sass files, minifying JavaScript, optimising images, or running tests.

Stage 1: Parsing

During the first stage of the build, prior to any processing, the input directory is copied into an in-memory tree structure. As the tree is constructed, each node is also parsed according to its file type. I chose to store the tree fully in memory for two reasons: firstly, it removes any I/O overhead since it requires the minimum possible number of I/O operations (provided that all files are actually used in the build), and secondly, it makes the implementation of the processing stage much simpler since it can take the form of the core function I mentioned earlier, mapping one in-memory tree structure to another.

The input tree structure is represented by the Node enum, which has variants for files and directories. Files also store their parsed contents, which are represented by the ParsedContents enum. These two enums are reproduced below:

pub enum Node {

File {

name: String,

contents: Vec<u8>,

parsed_contents: ParsedContents,

source: PathBuf,

},

Directory {

name: String,

children: Vec<Node>,

source: PathBuf,

},

}

pub enum ParsedContents {

Html(Vec<LocatableToken>),

Markdown(ParsedMarkdown),

Json(Value),

None,

}

The construction of the ParsedContents enum differs based on the file extension. HTML files are parsed into tokens, which are either raw HTML, variable template tags, or function template tags. Markdown files are converted to HTML at this stage using pulldown-cmark, and the ParsedMarkdown struct also contains their frontmatter, user-defined metadata about the page. JSON files are parsed using my own Humphrey JSON library, and this library is also used to internally represent variables. Files with any other extension do not have their contents parsed.

Variables are, at this stage, represented simply by their names. Functions are initially represented as RawFunctions, which contain the name of the function, its positional arguments, and its named arguments. These semi-parsed functions are then converted into executable functions using an extensible parser system that I created. In this system, each function type (such as for, dateformat, ifdefined etc.) has its own parser which is responsible for turning a raw function into an executable function. The parser implements the FunctionParser trait, and the executable function it creates implements the Function trait. Both traits also require the function to specify its name, which allows Stuart to identify which function parser to use for which raw function. Through this system, it will be easy to add function plugins in the future, since they can just be added to the global list of function parsers which are checked by Stuart.

The two core function traits are reproduced below:

pub trait FunctionParser: Send + Sync {

fn name(&self) -> &'static str;

fn parse(&self, raw: RawFunction) -> Result<Box<dyn Function>, ParseError>;

fn can_parse(&self, raw: &RawFunction) -> bool {

raw.name == self.name()

}

}

pub trait Function: Debug + Send + Sync {

fn name(&self) -> &'static str;

fn execute(&self, scope: &mut Scope) -> Result<(), TracebackError<ProcessError>>;

}

You may have noticed the TracebackError type in the above definitions - we’ll discuss that later in this post when we cover Stuart’s error handling system.

The result of the parsing stage is a tree structure of Nodes with their contents parsed, and this is then the input of the processing stage.

Stage 2: Processing

The processing stage is the core of Stuart, where Nodes are converted to OutputNodes. The OutputNode type is very similar to the Node type, but it does not contain the parsed contents. Instead, it contains the output of the processing stage, which is later saved to disk in the third and final stage.

For each file in the tree, the Node::process function is called, which, if successful, returns an OutputNode. The execution of this function differs based on the file’s parsed contents: for HTML and Markdown files, the template engine is used, and for all other files, the contents are simply copied over. Since Markdown is processed in the parsing stage, it is treated as HTML with additional metadata in this stage.

The Template Engine

One of the most important parts of a static site generator is its template engine. This is responsible for combining data from a number of sources with the template pages to produce the final HTML output. This is perhaps easier to understand with an example. Consider the following template for a Markdown blog post:

{{ begin("main") }}

<h1>{{ $self.title }}</h1>

<h2>{{ $self.author }} • {{ dateformat($self.date, "%d %B %Y") }}</h2>

<ul>

{{ for($tag in $self.tags) }}

<li>{{ $tag }}</li>

{{ end(for) }}

</ul>

{{ $self.content }}

{{ end("main") }}

When combined with the data from the frontmatter of a Markdown file, which is referred to as $self in the template, this could produce the following HTML:

<h1>Building Stuart, a blazingly-fast static site generator</h1>

<h2>William Henderson • 03 September 2022</h2>

<ul>

<li>project</li>

<li>rust</li>

<li>deep-dive</li>

</ul>

A few weeks ago, I watched...

The begin("main") and end("main") functions in the template above indicate how the content should be placed in the root template, which is a file called root.html used to wrap all other templates. It defines where each section of the template should be placed in the overall HTML structure using the insert function. A very simple example of a root template could look like this:

<html>

<body>

{{ insert("main") }}

</body>

</html>

Stuart’s template engine stores all variables as JSON behind-the-scenes, and it uses a stack-based system to keep track of the current scope. When a variable is referenced in a template, the engine searches down the stack to find its value. Functions are called using the Function trait’s execute method, which was discussed earlier. This method is passed some information about the current state, and it can modify this information as necessary.

Some functions take control of the processing of tokens for a short period of time, in particular those which change the scope. For example, the for function keeps a note of the current position in the token iterator, and creates a new stack frame with the initial value of the loop variable defined. It then processes tokens itself, and upon detecting that the stack frame it created has been popped by the end(for) function, it jumps back the start of the loop and repeats the process for every value of the loop variable. By allowing functions to do this, they can work together to manipulate the template in a much more complex way. While the built-in functions are very limited in functionality at the moment, a plugin system will be implemented in the future to allow users to create their own functions in Rust.

If you’re interested in learning about the different built-in functions that Stuart has, you can visit the project on GitHub.

Stage 3: Saving

Once the tree of Nodes has been successfully processed and turned into a tree of OutputNodes, these need to be saved back to the disk. This is done with a simple pre-order traversal of the tree, creating directories and files as necessary. Stuart can also be configured to remove the need for .html extensions on files by placing each HTML file in its own directory, and creating an index.html file in that directory.

Bonus Stage: Error Handling

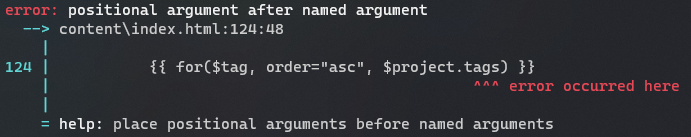

We’ve discussed what happens if everything goes well, but what if an error occurs? Descriptive and helpful error messages are one of my (many) favourite things about Rust, so I took inspiration from them when designing the error handling system.

Every error that can occur during each stage is represented by a variant of either the ParseError enum for stage 1, ProcessError for stage 2, or FsError for stage 3. All of these types implement the StuartError trait, which defines error messages and help text, as well as additional formatting information to use with termcolor. The trait is reproduced below:

pub trait StuartError {

fn display(&self, buf: &mut termcolor::Buffer);

fn help(&self) -> Option<String> { None }

fn print(&self) {

// automatically implemented to prefix `self.display()`

// with the string "error: " in red text

}

}

While these three enums are capable of producing simple error messages and help text, they are not capable by themselves of advising the developer as to where the error occurred. To solve this, Stuart uses a generic TracebackError type, a simplified version of which is shown below:

pub struct TracebackError<T: StuartError> {

path: PathBuf,

line: u32,

column: u32,

kind: T,

}

This type uses the StuartError implementation of the error to generate its error message and help text, and then formats it with the path, line, and column of the error. It also opens the file at the path and prints the line of code where the error occurred, indicating the column as well.

This design also makes it very easy to add more error types in the future, as it just involves adding a new variant of the corresponding error enum and defining its error message and help text in the big match statement that is the trait implementation.

Performance and Benchmarking

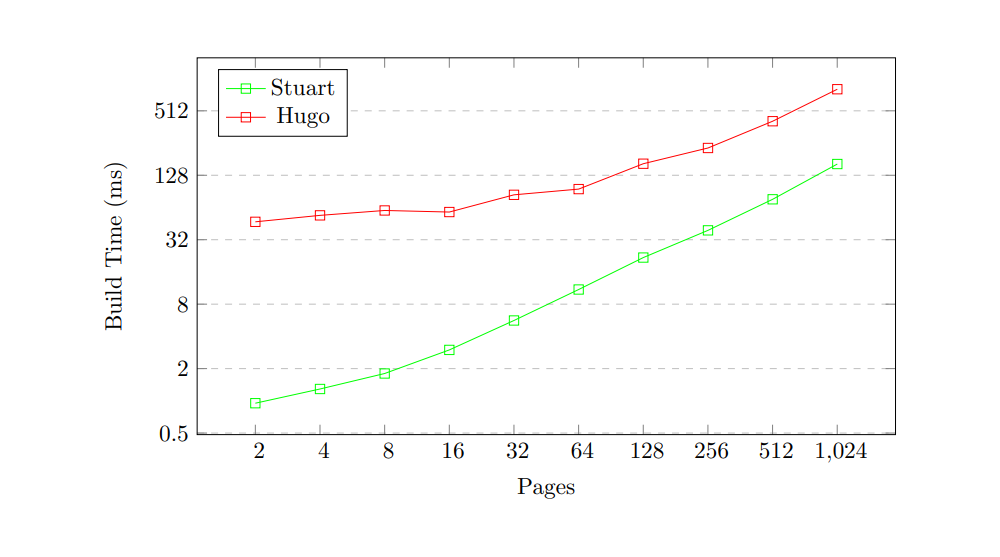

Now you’ve seen how Stuart works, let’s take a look at whether it meets its original goal of dethroning Hugo as the “world’s fastest” static site generator. As well as testing the build times of both SSGs, I wanted to also see how they scale as more pages are added to the site.

I read an excellent article about comparing SSG build times by Sean Davis recently, and I decided to use a similar benchmarking method to compare Stuart and Hugo. Both sites will have the same number of pages, starting at 2 and doubling until 1024, with each page consisting of three paragraphs of Lorem Ipsum text without any styling. There will also be a homepage which lists all the other pages. The timing will be handled internally by Stuart and Hugo’s built-in benchmarking tools, and the results will be averaged over 100 runs. I ran the benchmarks on a fairly powerful Linux computer, but the actual build times are far less relevant than the comparison between the two SSGs.

Build Times

First, let’s look at the build times for Stuart and Hugo as the number of pages increases.

As you can see, Stuart consistently beats Hugo in build times by a huge margin, especially when the number of pages is very small. My hypothesis is that since Hugo is a much more complex project, the overhead of setting up the build system and parsing the configuration is far more noticeable when the build takes less time.

For a site with two pages, Stuart takes just 0.95ms to build the site, compared to Hugo’s 47ms. This is nearly 50 times faster! As the number of pages increases, the build times of both SSGs scale similarly and the relationship between the two becomes more obviously linear. At 1024 pages, Stuart takes 162ms to build the site, compared to Hugo’s 814ms. This is still 5 times faster, and extrapolation would indicate that this is probably a fair estimate of the difference in build time between the two SSGs as the number of pages continues to increase.

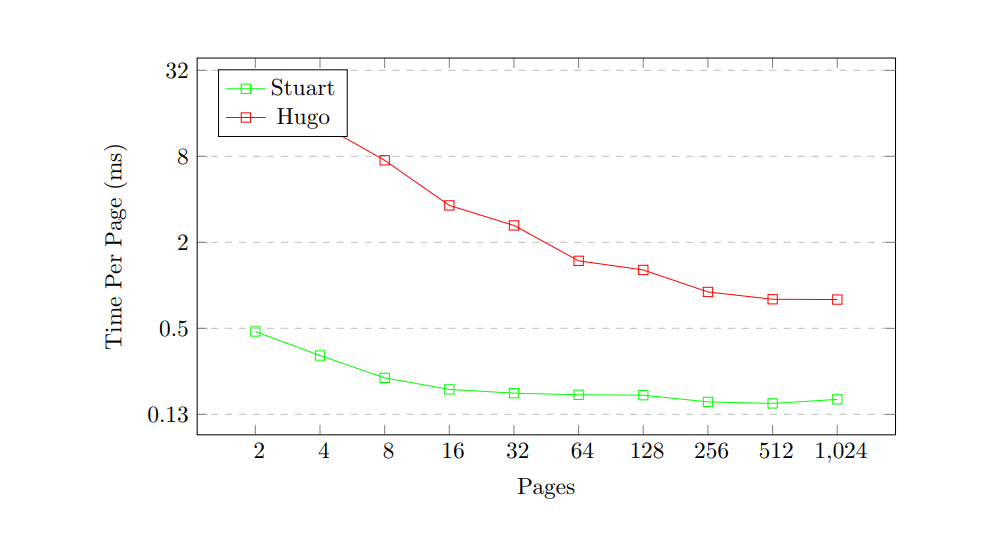

Time Per Page

Another metric commonly used to benchmark static site generators is the time it takes per page. To calculate this, I simply divided the build time by the number of pages for each point.

Hugo advertises on its website that it takes less than 1ms per page, and this benchmark shows that, at least on my machine, this is only true when the number of pages is fairly high - interpolation of the data would suggest that a minimum of around 200 pages is needed for this claim to hold.

Migrating This Blog to Stuart

I built this blog back in May using Gatsby - you can read about that process in my first blog post - and while it worked well, it did always take a long time to build. I decided to migrate it to Stuart to test it out in a production environment, and if you’re reading this - it worked!

Much of the migration was very simple, as it was just a case of copying the markup for the homepage from the JSX files into HTML files, and copying the Markdown blog posts across. The Gatsby blog used Sass for styling, and I wanted to keep using it, so I had to make use of Stuart’s custom build scripts to compile the Sass files. I created an onPreBuild.sh script which simply runs sass with some configuration options to achieve this, and it worked perfectly.

Dynamically Generating Embed Images

In my opinion, one of the coolest features of my blog is its automatically-generated embed images that show the title and date of each blog post in a style consistent with the blog whenever a link is shared. Here’s the embed image for this post:

I wrote a blog post about how I implemented this for the Gatsby blog using Puppeteer and a Node.js script, and I found that the easiest way to migrate this to Stuart was to use the same approach. I copied across most of the code from the Gatsby blog, and I updated it so that instead of using GraphQL to query the blog posts, it uses Stuart’s metadata system to get the same information. Since, unlike Gatsby, a Stuart project is not an NPM package, I had to create a small NPM package called embed in the scripts directory to handle JavaScript dependency management. I also created an onPostBuild.sh script which installs the dependencies and runs the Node.js script:

cd scripts/embed

npm i && npm start

Deployment

My blog is hosted on Cloudflare Pages, which supports custom build commands for static site generators. It was a little bit fiddly to get the configuration right, as you can’t exactly SSH into the build environment to debug! Eventually, I got it working by using the following build command, so I can officially say that Cloudflare Pages supports Stuart:

curl -L https://github.com/w-henderson/Stuart/releases/download/v0.1.0/stuart -o stuart && chmod +x stuart && ./stuart build

One last thing I had to do was set the NODE_VERSION environment variable in Cloudflare Pages to a newer version, as the default version is 12.18.0 which doesn’t support ES modules.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Stuart seems to have earned its title of “blazingly-fast”, and I’m very happy with how it’s turning out. There’s still a lot of functionality left to implement, not to mention all the testing that needs to be done too. It has the potential to overtake Humphrey as my biggest project - that is, if I have any free time once I’m at university!

I hope you enjoyed this post, and if you’re interested in trying out Stuart, you can find it on GitHub. If you found this post useful, please consider sharing it with others who may be interested!