For the last 12 weeks, I’ve been working at Nutanix as a Software Engineer Intern on their hypervisor team in Cambridge. When I wasn’t playing chess, eating free food, or punting on the Cam, I was working on a project to modernise live migration of virtual PCI devices, and in this post I’ll be talking about my experience and what I learned.

We’ll start with a bit of background before diving into the technical details of my project, and then I’ll talk about what else I got up to during the internship and what I learned from the experience.

Me in the Nutanix Cambridge office

Background

Nutanix provides businesses with a platform to run VMs anywhere, from on-premises data centres to public clouds, with a single unified control plane. A core part of this platform is the hypervisor, AHV, which is based on the open-source KVM hypervisor and uses QEMU for device emulation. While it’s a pretty big company (with 5000+ employees around the world), the core hypervisor team in Cambridge is relatively small, which meant I got to experience both the massive corporation vibe and the small team vibe. This distinction was particularly noticeable when we went to a UK-wide company meeting in London, but I’ll get to that later!

I should also put a brief disclaimer here that I’m not being paid to write this post and all opinions are my own. I did indeed write a post for their blog with the support of their marketing team, which should be up soon, but this is not that - there’ll be nothing removed for “not being in the Nutanix voice” here!

What did I do?

My project was to define, implement, and test a new protocol for live migration of virtual PCI devices as part of the open-source vfio-user project. vfio-user is a userspace adaptation of the VFIO kernel facility (which allows userspace processes to directly access and control PCI devices) and uses a UNIX socket instead of ioctls to communicate between a virtualised device process and the QEMU process running the VM. AHV uses vfio-user to provide lower-latency virtualised NVMe storage to VMs, but I think that’s all I’m allowed to say about the internal use case! As well as updating the protocol, I had to update Nutanix’s open-source implementation, which is called libvfio-user and is written in C.

A lot of the complicated migration logic, like choosing a destination host and copying the VM’s memory, is handled by other systems that I luckily don’t have to understand, but everything to do with the migration of virtual devices is handled by vfio-user.

In the context of migration, vfio-user liaises between the VM controller (known as the “vfio-user client”, which is responsible for the migration of the VM as a whole, including transferring data to/from the other host involved) and the virtualised device process (known as the “vfio-user server”, which is responsible for the migration of the specific device, including serialising/deserialising its state). It does this by providing the client with an API over a UNIX socket that it can use to send commands to the server, executing a callback on the server which performs the specific action (for example configuring DMA or changing migration state). Since vfio-user is a general-purpose solution for any PCI device (like VFIO), it doesn’t know anything about the device it’s migrating, so the callbacks are provided by the device-specific code.

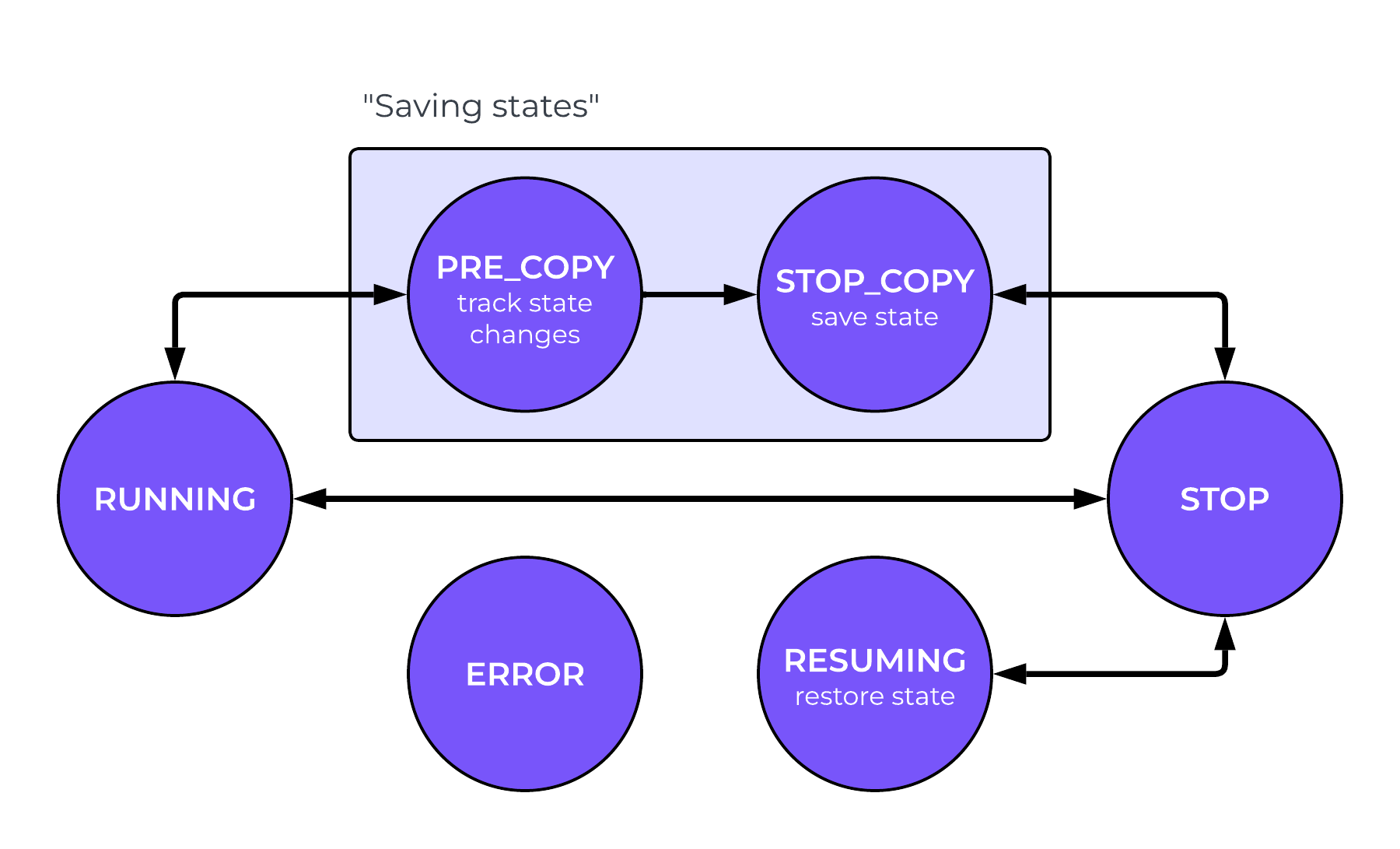

Both the former and my new live migration protocols involve five migration states, although the transitions between them and the underlying implementations are fundamentally different. The states are:

- Running: The device is running normally.

- Stop: The device is stopped and cannot change any state.

- Pre-copy: The device is running normally, but tracking any changes to its state while beginning to transfer its state to the destination host.

- Stop-and-copy: The device is stopped and is completing the transfer of its state to the destination host.

- Resuming: The device is stopped and is receiving its state from the source host.

The Old Protocol (v1)

The previous live migration protocol in vfio-user is known as “v1” (or “v1 upstream” to differentiate from NVIDIA’s weird private protocol that is sometimes called “v1”, but we won’t worry about that here), and is based on a PCI region called the migration region, which is used to store both migration state and data. When the client wants to change state, it makes a write like any other to a certain register in the migration region, and this write is identified by vfio-user which verifies the transition is valid, makes the appropriate internal changes, and then calls the device-specific callback to perform the action (e.g. RUNNING -> PRE_COPY likely enables dirty page tracking and starts serialising the device state to the rest of the migration region). When the client wants to read this state to send to the destination, it first reads the pending_bytes register to see how much migration data is remaining in total in this state, then reads the data_offset register to see where in the migration region the next chunk of data is (and performing this read also causes vfio-user to put the data there and set the data_size register), and finally reads the data itself. This is repeated until pending_bytes is zero, at which point the client can transition to the next state (e.g. PRE_COPY -> STOP_COPY, stopping the device to copy the dirty pages, or STOP_COPY -> STOP to finish the migration). A similar process in reverse is used to load new device state on the destination.

Given that the migration data is effectively a stream, it is a bit weird to interact with it through a PCI region with reads and writes just like any other data, especially given the extensive side effects these operations perform within the migration. That’s not to mention the fact that the migration state is also just stored in a special part of this region.

These issues perhaps contributed to the fact that migration v1 saw very little adoption, so much so that the open-source community decided to completely replace it with a new protocol, which is what I was implementing for vfio-user.

The New Protocol (v2)

The new protocol entirely removes the migration region, replacing the device state bitmap with an internal finite state machine, and making the transfer of device state use new MIG_DATA_READ/WRITE commands with stream semantics over the UNIX socket. Additionally, indirect state transitions are supported, with the server automatically identifying the correct sequence of transitions to take through the FSM. For example, in v1, if the server wants to transition from RUNNING to STOP_COPY instead of going through PRE_COPY, the server has to know how to perform this exact transition (i.e. stop the device and start migration data transfer). In v2, this transition is automatically broken up into RUNNING -> STOP, which stops the device, and STOP -> STOP_COPY, which starts migration data transfer. This means that the server only needs to know how to perform the individual steps.

The vfio-user migration v2 FSM, showing the transitions implemented by the server

How does the server know which path to take through the FSM then, you might ask? Well, it follows two rules:

- Take the shortest path, but

- Don’t have any “saving states” (states where data is transferred, i.e.

PRE_COPYandSTOP_COPY) as intermediate states

In the actual libvfio-user source code, this is implemented as a matrix of current states against target states, where the next state in the correct path is given by next_state[current][target]. However, since states could plausibly be added or changed in the future (especially given that this has happened before, with PRE_COPY being a relatively new addition to VFIO), I decided it would be fun to use some of the knowledge from my algorithms course to write a test to calculate the shortest paths between all pairs of states in the FSM using BFS to check that the matrix is correct.

Another thing that changed in v2 is the dirty page tracking API, which is used in the PRE_COPY state to keep track of which pages are dirtied when performing DMA. There is much more flexibility available in v2, as well as it becoming a DEVICE_FEATURE rather than its own message type. Specific IOVA ranges can be tracked at a custom power-of-two page size, and the report detailing which pages have changed can be requested at any page size, with the server automatically converting it to the requested size (by duplicating bits or ORing multiple bits together). This was surprisingly simple to implement, but there was a fair bit of debate about how exactly to structure the code, so there was quite a lot of refactoring and re-refactoring involved!

What else did I do?

Of course, the work wasn’t just sitting at my desk writing code:

Big Meeting in London

Fairly early on in the internship, I had the opportunity to join the team on a trip to a UK-wide meeting at the London office, where the CEO Rajiv Ramaswami (who had flown in from the US) and some of the top UK people discussed very important business things while we sat at the back and nodded at appropriate times. It was an amazing insight into how a big international company is run at the very top level, and one I certainly didn’t think I’d get as a lowly intern!

The view from the London office balcony

After the big meeting, we (just the Cambridge team) had the chance to sit down with Rajiv to discuss our team, our projects, what we need from other teams, and other top secret discussion topics. The meeting was really productive and I think that both Rajiv and the team got a lot out of it - I was so pleased to have gone. (There was free food too)

Free Food

On the topic of free food, there was lots of it. Some of the larger offices have on-site catering, but since the Cambridge office is a bit smaller, we have a weekly lunch budget for ordering delivery which is supposed to last two days. However, between people working from home, being on holiday, and the budget itself being surprisingly generous, it usually lasts three or four days (and in August, often all five!). It was really fun to try food from lots of new Cambridge restaurants, and sitting down with the team in the slightly-too-small meeting room for lunch was always a fun vibe.

Chess

I’m not exaggerating when I say I think my chess ability played a large role in me getting the internship. I was interviewed by Felipe, who is in charge of the hypervisor team, and during the interview, alongside my projects and knowledge, he was very excited to ask me about chess. Chess was listed at the bottom of my CV as an “interest”, mostly just to humour my dad who told me I needed to show that I’m a real person, but it turned out to be possibly the most important part of my somewhat bare first-year CV! Felipe is insanely good at chess, and although he is always really busy, he still found time to play several games with me (I even won a few!) and give me a bit of coaching over the course of the internship. I also played a lot with Tom, one of the other interns, and we had so much (maybe ever so slightly too much) chaotic fun playing some absolutely horrendous games.

Punting and Steak

Towards the end of the internship, one of the VPs came over from the US to visit the Cambridge office, and some of us took him punting on the Cam before going out to dinner at a steak restaurant. This was actually the second time we went punting as a team, but since this time it was an official team activity, it was paid for! Afterwards we went to a really nice steak restaurant in Cambridge and ended up talking about interview questions, which, given that I’m currently in the midst of applying for internships for next year, gave me some extremely valuable insight from the other side of the table.

One of the several Bridges of Sighs I saw this summer

What ELSE did I do?

Despite working full-time and only having six days of holiday during the 12 weeks, I managed to fit in a lot of things (mostly by sacrificing sleep to get 6am flights, which was absolutely worth it). For the first time in my life, I had both time and money, and I made the most of it. I spent a weekend in Cologne and Copenhagen (Copenhagen is one of the best cities I’ve ever visited), had a family holiday in Venice over a long weekend, met up with friends in London, visited my grandparents in Cornwall, and even went to Canada for a long weekend to see a Cambridge friend on his home turf! This isn’t a travel blog so I won’t waffle too much, but I had an amazing time and I’m so glad I managed to make the most of my time off work.

Venice, Copenhagen, Cornwall, Niagara Falls

What did I learn?

I went into the internship knowing no more than my operating systems course had taught me about virtualisation and the Linux kernel, and with no experience at all with C. Thanks to the amazing support of the team, especially my mentors Thanos and John, I got going quickly and was able to get the whole project completed and merged into master before the 12 weeks were up. I’m especially grateful for the comprehensive and detailed code reviews they gave me, which were by far the best way to really learn a new language - I’ll have to update this blog post! I would’ve liked to review some of their code too, but there wasn’t really an opportunity for that, so maybe that’s something that could be improved for future interns.

I also learnt a lot about how the open-source development process works for big projects like QEMU and the Linux kernel. Having liaised with the QEMU maintainers to fail to get my new spec merged, I now understand just how enormous and complex these projects are from the management side as well as the technical side. Hopefully one day they stop ghosting me! (I’m joking of course, they gave some extremely helpful feedback and they are very busy people)

Finally, I learnt a lot about how a big company like Nutanix works, and how all the different teams and managers and executives fit together to make a company that works. It really made me realise just how massive of a task it is to organise thousands of people all working towards the same goal, and being a part of that for three months was a fantastic experience.

Conclusion

Reading this back I’m realising it doesn’t sound that much less marketing-y than the actual edited-by-the-marketing-department blog post, but oh well, I did have a great time. I’m so grateful to the team for the opportunity to work on such an interesting project for the summer and get some valuable work experience, and I’m looking forward to keeping an eye on the project’s GitHub and seeing how my code develops in the future. (Sorry for the inevitable bugs left in there!)

Thank you for getting to the end of this post, and I hope you enjoyed it! Please do get in touch if you have any questions or comments, especially if you’re a recruiter with an interesting internship opportunity for next summer ;) (worth a try, right?)

That’s it for now, I’ll see you in the next one!